Alina Cohen Apr 17, 2020

J. Paul Getty Museum

Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

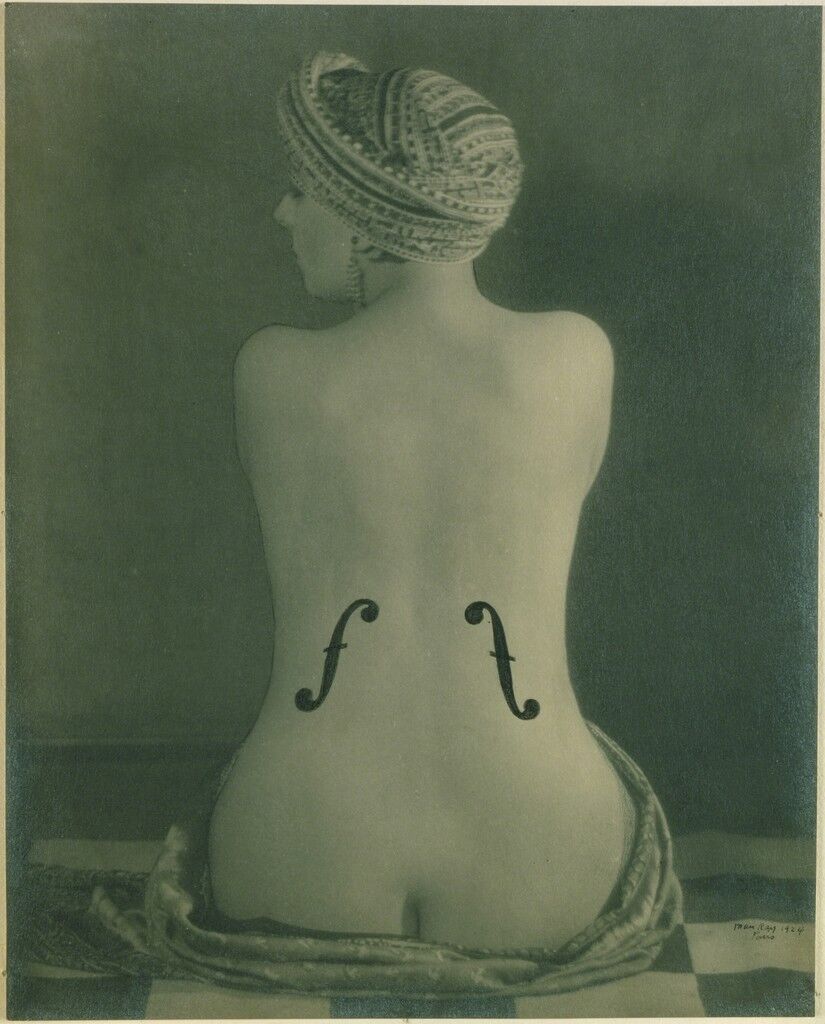

In 1940, famed Surrealist artist Man Ray fled war-torn Europe for the sunny streets of Los Angeles. Threats of persecution and violence were shattering his avant-garde community in Paris, turning many of his friends and fellow artists into refugees. The turmoil also marked the end of the Surrealists’ primacy in Western art. In less than a decade, American Abstract Expressionism would dominate the art press, and Life magazine would famously ask, “Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

Yet the story of Surrealism was hardly over. Man Ray’s new hometown offered the movement an afterlife. Though Los Angeles was slow to embrace work by the photographer and his coterie, the city created new opportunities for them to work in safety. Its oddities and charms were ultimately a good fit for the European émigrés who adored eccentricity. As Man Ray famously said, “There was more Surrealism rampant in Hollywood than all the Surrealists could invent in a lifetime.” Los Angeles also gave the group unique patronage, access to the film industry, and connection to younger artists who would celebrate their legacy in strange new ways.

A growing audience

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

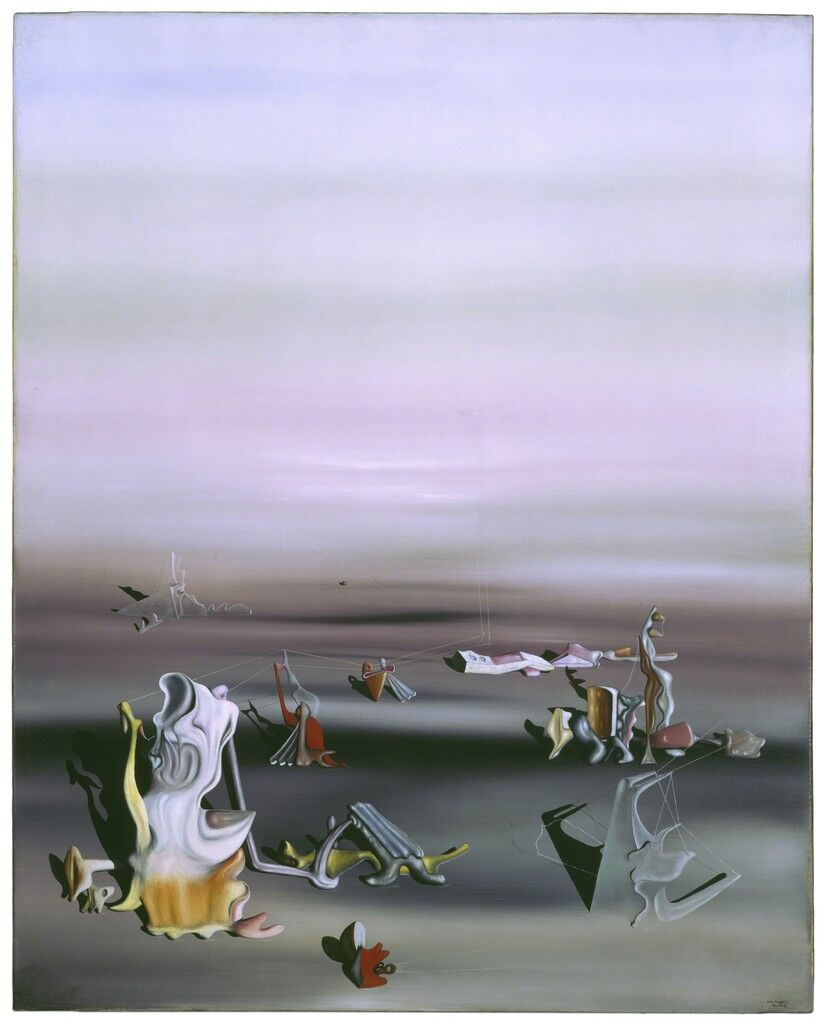

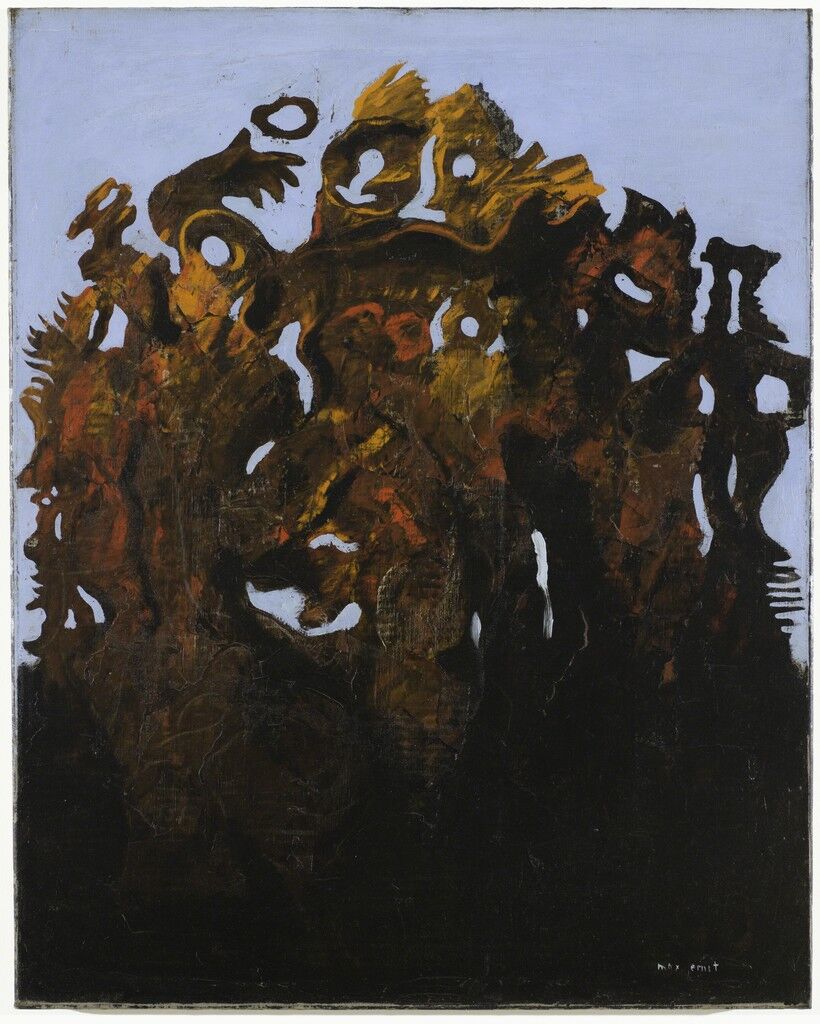

In the essay “Surrealism on the Rise: the Copley Galleries and Joseph Cornell in Hollywood,” art historian Timea Andrea Lelik writes that Howard Putzel was “most likely the first dealer to link European surrealism to California.” Before World War II erupted, Putzel attempted to promote the movement through a number of exhibitions between 1935 and 1936. As the director of Stanley Rose Gallery, he showed work by Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, André Masson, and Joan Miró. But they never really caught on. Even when Putzel launched his own gallery in 1936, the West Coast appetite for his European avant-garde offerings seemed sparse.

Yet one collecting couple in Los Angeles was very engaged in such work—Walter and Louise Arensberg. Their tastes were so influential, legendary California-based curator Walter Hopps once called them the “most important collectors ever in the Western United States.” Longtime friends of Marcel Duchamp, the Arensbergs bought the artist’s famous canvas Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) back in 1919, when the country was still catching up to radical European art. Throughout the subsequent decades, Duchamp frequented their Los Angeles home. By the time of their deaths in the mid-1950s, the couple had amassed a collection that included work by Duchamp, Ernst, Miró, René Magritte, and Salvador Dalí.

![[Marcel Duchamp and Raoul de Roussy de Sales Playing Chess]](https://d7hftxdivxxvm.cloudfront.net/?resize_to=width&src=https%3A%2F%2Fd32dm0rphc51dk.cloudfront.net%2FH4LdA0oPPS7_sVPWxFa3bw%2Flarger.jpg&width=1200&quality=80)

J. Paul Getty Museum

In other words, there was patronage to be found among California’s palm trees. The Arensbergs became such close friends to the Surrealists that in 1946, they hosted the double wedding between Man Ray and dancer Juliet Browner, and Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. Florence Homolka’s portrait of the unusual celebration features the loving foursome reclining against one another, their heads and shoulders intertwined.

The year 1948 proved to be a major one for Surrealism in Los Angeles. The Modern Institute of Art opened its doors with an exhibition that included work by Duchamp and Miró. Meanwhile, the short-lived Copley Galleries mounted Man Ray’s first solo show in Los Angeles, which attracted an all-star guest list that included Harpo Marx, Fanny Brice (theinspiration for the 1968 film Funny Girl), Hans Hofmann, Isamu Noguchi, Igor Stravinsky, Aldous Huxley, Henry Miller, Luis Buñuel, Jean Renoir, and Otto Preminger. The amity between the worlds of entertainment and fine art blossomed.

Surreal cinema

If Man Ray easily found fiscal supporters, he had a harder time breaking into the mainstream film world. Though he worked as an art director for Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), starring Ava Gardner, his career in the industry never flourished.

Yet the artist—who was an experimental filmmaker in his own right—did find a receptive community at American Contemporary Gallery. The Hollywood venue screened his work, in addition to the dreamy animations of Oskar Fischinger.

Avant-garde, Surrealist-tinged cinema was blooming in the city. Maya Deren finished her shadowy, silent Meshes of the Afternoon in 1943. Kenneth Anger made his trippy Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome,starring occultist poet, artist, and actress Marjorie Cameron, in 1954. Cameron’s own work was similarly influenced by the movement. Curator Harmony Murphy described her work as being involved in “the unconscious, dreams, sexuality, and the occult,” relating back to André Breton’s movement-defining “Surrealist Manifesto” (1924).

The most famous Surrealist collaboration with Hollywood occurred in 1945, when Alfred Hitchcock commissioned Salvador Dalí to design a dream sequence for his upcoming film Spellbound (1945). The haunting result features floating eyes, a card table, a masked man, and long shadows—classic Dalí. The Surrealist’s engagement with the unconscious complemented Hitchcock’s own interests in psychoanalysis and repression. Dalí also briefly worked with Walt Disney the next year, though the collaboration wasn’t made public until after the artist died.

“What’s most exciting about the Surrealist legacy in Los Angeles is that it was here that it penetrated the mainstream film industry,” said Los Angeles–based artist Max Maslansky. In 2016, Maslansky organizedan exhibition at Richard Telles Fine Art that focused on Surrealism’s long-lost history in the city, titled “Tinseltown in the Rain: The Surrealist Diaspora in Los Angeles 1935–69.” Maslansky also noted that Disney made it a point to hire European émigrés who’d been exposed to Surrealism and “could bring these ideas into animation and film.”

Heirs apparent

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art …

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

In an essay published in On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900–1950 (1996), art historian Susan M. Anderson describes two factions of Surrealism being developed out West. She writes, “While in northern California surrealism developed toward abstract expressionism, in southern California it developed toward geometric abstraction.” In 1934, Los Angeles–based painters Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg founded Post-Surrealism, a movement that responded to their European predecessors. Joining their ranks was a young Philip Guston.

Lundeberg’s spooky figurations feature the trademark elements of European Surrealism—a clock, a sandy landscape, a painting within a painting—with a domestic, feminine touch. Feitelson similarly embraced the movement’s dreamy symbology. When the pair veered into hard-edged abstraction, Feitelson translated his bold palette to soaring volumes, while Lundeberg painted mystical compositions in tranquil, pastel hues.

The pair’s work recently appeared in an exhibition at Kasmin Gallery titled “Valley of Gold: Southern California and the Phantasmagoric,” which opened on March 5th and has been closed indefinitely due to COVID-19. In the show, Feitelson and Lundberg create a link between the European avant-garde and younger artists such as Ed Ruscha—whose wry text-based works share an affinity with Magritte’s wordplay—and Robert Therrien, whose giant furniture evokes an Alice in Wonderland–inspired dream.

Curated by Harmony Murphy and Sonny Ruscha Grande, the show posits a loose aesthetic lineage that starts with the Surrealists and ends with contemporary artists. Instead of declaring explicit connections, as Murphy writes in the exhibition essay, the show posits “a traceable legacy of influence” revealed in “a flicker of mischievousness, an uncompromising approach,” and a “re-writing of rules.”

The paintings of Luchita Hurtado and Lee Mullican help tell the story, as well. Mullican co-founded the Dynaton group of Post-Surrealist artists in San Francisco in the late 1940s. The movement enjoyed a major exhibition in 1951 at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Over the next decade, Hurtado and Mullican settled in Los Angeles, taking Dynaton aesthetics with them. Hurtado’s spare, uncanny landscapes exemplify her avant-garde influences.

In her essay for the Kasmin exhibition, Anderson wrote that Surrealist activity in Southern California “culminated in 1966, when a Magritte retrospective” came to town. Walter Hopps brought the show, which was organized by the Museum of Modern Art, to the Pasadena Art Museum during his final year as its director.

Artforum, which was then based in Los Angeles, published an issue devoted to the movement. “Surrealism” danced across the cover in bold red lettering against a backdrop of bubbles: an artwork titled Surrealism Soaped and Scrubbed (1966) by Ed Ruscha. “While tipping his hat to the legacy of European surrealism, Ruscha also acknowledged its contribution to the pristine aesthetics of Los Angeles’s finish fetish and light-and-space art,” wrote Anderson, referencing the major veins of California minimalism.

By the 1960s, Surrealism had permanently infiltrated the West Coast subconscious, burbling into its text art, sculpture, performance, and painting. “Los Angeles is isolated from these intellectual centers,” said Murphy. “Most postmodern artists think of themselves as outliers or cowboys. Left of center. That’s similar to the way that the Surrealists saw themselves.”

Alina Cohen is a Staff Writer at Artsy.